By all accounts, HEU’s 1996 convention was contentious and stormy. Members of the union’s four equity caucuses, along with the Provincial Executive, prepared for months to rally support for a motion that would enshrine these “working groups” as standing committees, and empower them to make formal and lasting change within HEU.

The convention floor

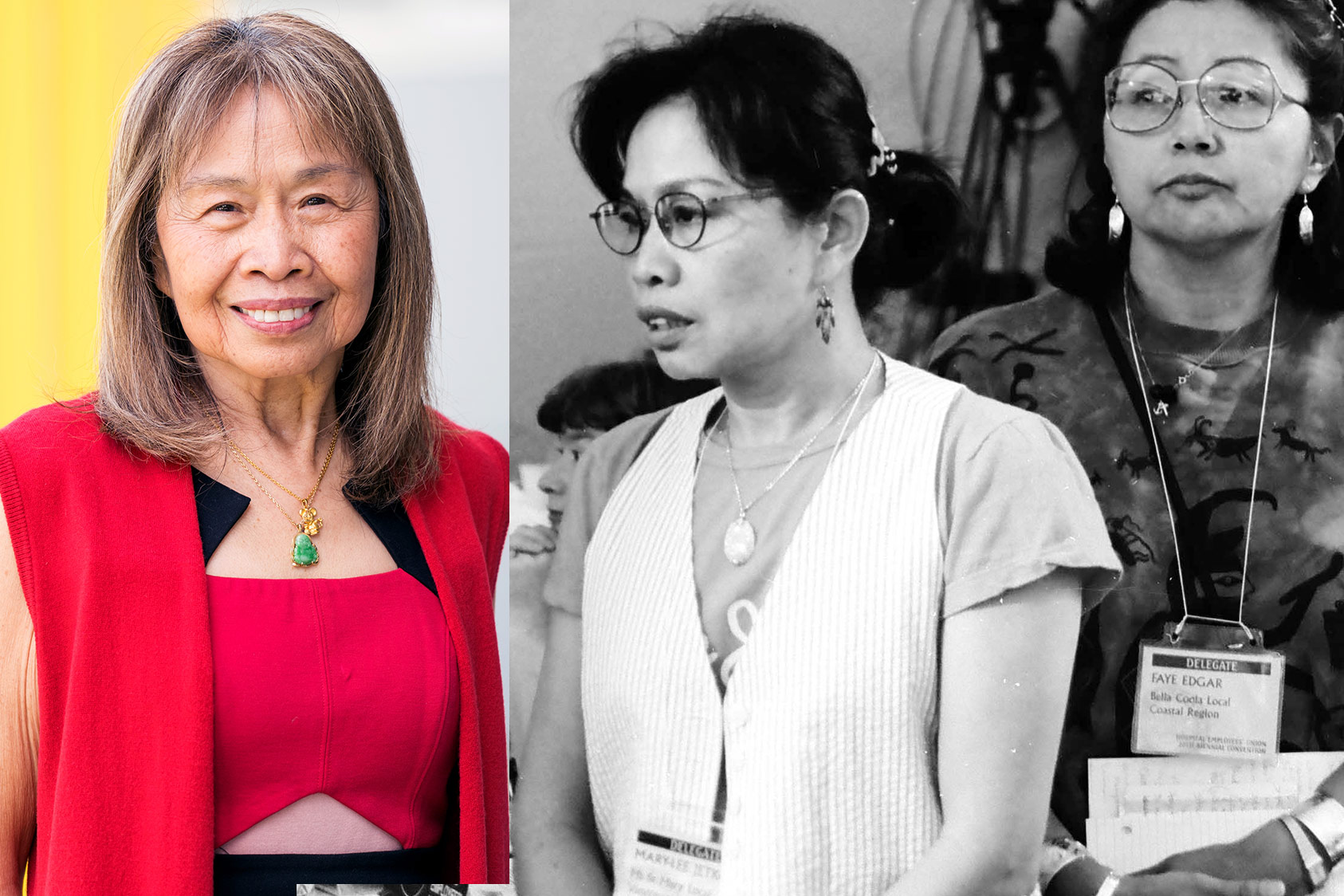

Mary Lee Jetko remembers the tears she shed at that convention.

A care aide at the time, Jetko took to the mic to speak in favour of the motion, and shared her experiences of racism with those in attendance.

“This became a long, emotional battle,” she tells the Guardian, 25 years later. “A lot of members came to the mic, and told their stories of how they were discriminated against at the workplace.”

But not everyone saw eye-to-eye, and some delegates were enraged by the idea of HEU dedicating resources toward marginalized groups.

“Some of the members were opposed to the idea,” Jetko recalled. “Some members were saying that we were just another ‘special interest’ people.”

Jetko, who is Chinese-Filipina Canadian, was a member of the Ethnic Diversity working group. Other caucuses, at the time, included Gay Men and Lesbian, First Nations, and People with disAbilities.

By passing a motion to enshrine these working groups into permanent standing committees in HEU’s Constitution & By-Laws, these committees would be eligible for funding and to send a delegate to future conventions. Their mandate would be to increase the participation of marginalized members within HEU, and to advise on programs and policy to eliminate inequality within the union and the workplace

Naming racism

Jetko got involved with HEU after moving to Canada with her husband in the 1980s. At her workplace, Mount St. Mary’s Hospital in Victoria, she faced bullying and slurs from patients and colleagues.

In one instance, a patient hit her repeatedly, yelled racial slurs, and told her to “get out.” In another, Jetko says a colleague double-parked her car, and refused to move her vehicle until two hours after Jetko’s shift had ended.

Growing up in the Philippines, Jetko faced racism and bullying for being half-Chinese, but says the discrimination was far worse when she came to Canada. She credits the HEU for empowering her with the words to describe her experiences.

“I realized when I came to Canada, about all the racism I was getting,” she said. “If I didn’t join the union, I still wouldn’t have known it.”

Despite the need for action against racism and discrimination, passing the motion to formalize the equity groups wasn’t easy.

Endless debate

Mary LaPlante, who was HEU’s financial secretary at the time of the 1996 convention, remembers the horror of watching delegates on the floor heckle the equity committee members as they spoke in favour of the motion.

“Some of our members weren’t very respectful when these committees were being created,” said LaPlante. “People were up at the mics screaming at them, other people were crying. It was quite an emotional time.”

While LaPlante wasn’t directly affected by issues of racism, ableism and homophobia, she knew the equity committees were needed, and was tasked with making sure equity-seeking members were able to access the convention.

Debate on the floor over the motion felt endless, she said. “We went through many, many hours and re-tabling it and bringing it back, changing it in some little form.”

LaPlante also remembers the restlessness away from the floor.

“I can clearly remember, I can hear people screaming at one another in the hallway on a break, because they didn’t support what was going on.”

Success in unity

Ultimately, the motion to establish permanent equity standing committees was passed by a two-thirds’ majority.

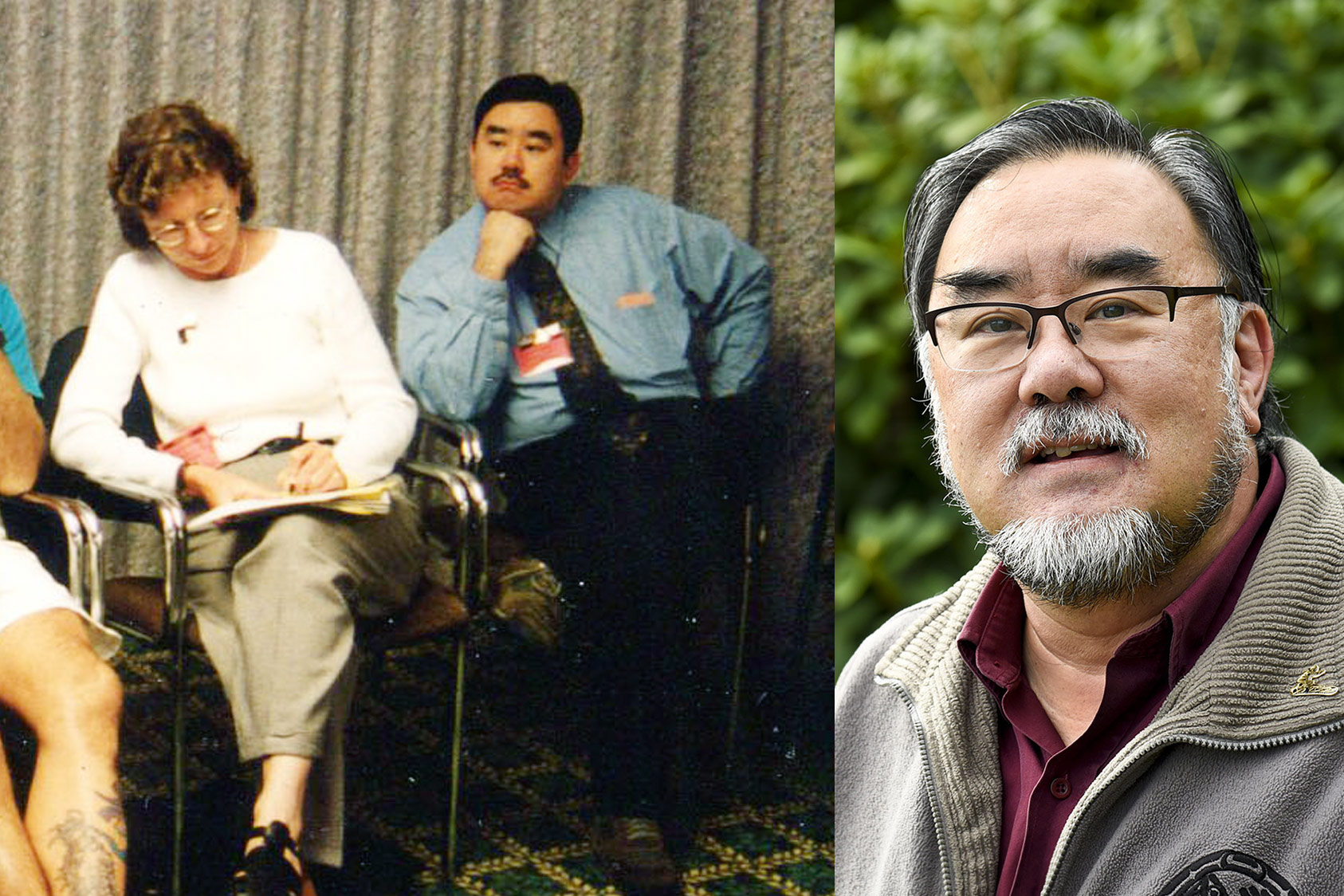

Roger Kishi, a member of the Ethnic Diversity committee from its founding, can clearly recall the chaos of the 1996 convention.

He said it was a “rollercoaster” because even after the motion passed, some delegates introduced a motion of reconsideration. This meant the motion came back the next day for debate and another vote.

“It was a very restless night, I didn’t get very much sleep,” said Kishi.

Unity between the four committees is what pulled them through, recalls Kishi, who is Japanese-Canadian and worked as a security supervisor at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver from the late 1980s to the early 2000s.

“The caucuses were working together to achieve this goal,” he said.

Shared teachings

After the motion to formalize the working groups as standing committees passed, the committees’ influence increased, and in the years that followed, their messages became part of shop steward training.

A quarter century on, LaPlante still remembers the teachings she learned from the First Nations Standing Committee (now the Indigenous Peoples Standing Committee), and the stories of workplace discrimination she heard from members of the People with disAbilities Standing Committee.

“They taught me a lot,” said LaPlante. “In particular, they taught myself and others about being respectful.”

In the 1990s, for example, many non-Indigenous people didn’t understand the impacts of residential schools. “The HEU First Nations group was very, very vocal,” recalled LaPlante.

“They taught our other members what it was like to go through some of this hell that they went through, and what their parents went through.” They also shared ceremonial practices, and opening prayers at various HEU events.

Donna Dickison, a member of the St’Atl’Imx Nation, was part of the First Nations Standing Committee in the 1990s, and remembers the hard work of educating members about the past and present of Indigenous Peoples.

“It was a lot of explaining,” said Dickison, a former Vancouver-based care aide. “Introducing ourselves and who we are as a people and as nations, and what it was like for us going through residential school.”

Harmful misunderstandings

Dickison, a residential school survivor, says that a major land claim in B.C. had been settled around the time of the 1996 convention.

She remembers how the settlement increased animosity toward First Nations Peoples because some non-Indigenous people seemed to think it meant all First Nations people in B.C. had received large chunks of money – and undeservedly.

That resentment, said Dickison, spilled over onto the convention floor. “They figured that we all had the money and we all were rich, and it wasn’t that way,” she said.

“We had to explain to them that we’re all different nations and we all come from different places. And it was just the one nation that got everything (in the settlement).”

Dickison also remembers that she and other equity committee members were accused of seeking out more than they deserved at the convention.

“It was really hard actually because a lot of the members thought we were ‘special’.” But when the motion finally passed, it was a relief, Dickison said. “They accepted us, it was nice.”

Finding a voice

Dickison says that discovering there was space for her experiences within HEU was pivotal. “We were able to talk. It gave me the voice to talk and to know that I didn’t have to be ashamed of who I was.”

At residential school, Dickison had been taught to dislike the colour of her skin. But through the equity committees, she says she became proud of herself, discovered her voice, and began meeting new people.

“It gave me freedom, freedom to speak.”

Jetko also remembers how the equity committees helped empower her. In the years that followed the convention, she learned how to speak out against racism, homophobia and ableism.

Specifically, she remembers being better-equipped to correct others’ misconceptions about First Nations Peoples and people with disabilities.

“Some people, when I can hear them talking about them, I always go and tell them that, ‘No, don’t do that. You shouldn’t be saying that because we should all work together,’” said Jetko.

Looking ahead

Although Kishi hasn’t been involved with HEU in nearly two decades, he still sees room for growth among the equity committees.

Back in 1996, Kishi says that members of the equity committees had discussed lobbying for seats dedicated to equity-seeking members on HEU’s Provincial Executive. At the time, the 21-member executive was nearly all white, and more than half were men.

“We came to consensus that what we really wanted first was to establish the caucuses formally within the structure of the union, and then try and move forward to gain equity seats on the executive,” Kishi recalls.

“It was a goal, way back before the convention in 1996. It was, in the minds of some people, myself included, that there should be equity seats on the executive.”