Indigenous communities in B.C. were among the first to spring into action when the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

Recognizing the massive risks the virus could bring to isolated, under-resourced communities, local First Nations governments worked quickly to implement travel restrictions and encourage physical distancing.

While the restrictions were necessary, they placed a burden on people living where access to groceries, public transportation, and community and health services were already inadequate.

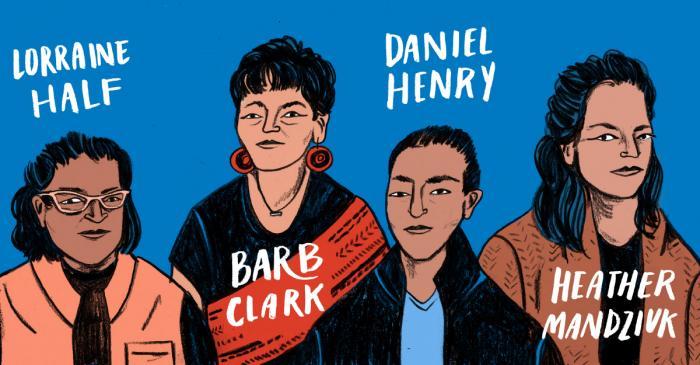

“People in my community would have to drive three hours to the next community to get toilet paper, which was limited to one package per family,” explains Lorraine Half, an HEU member from the Gitxsan Nation, who works with Gitxsan Health Society.

Half experienced firsthand how the pandemic created challenges in her work as an addictions counsellor, as phone and video check-ins often replaced in-person visits.

“So much of my work addressing trauma is hands-on and body-centred,” she explains. “When I can’t see a client physically, there is a loss of connection.”

Travel restrictions also increased social isolation for many.

“Phone calls were about all we could do to reach communities that had been closed off,” says Barb Clark, co-chair of HEU’s Indigenous Peoples Standing Committee. “Elders were feeling quite scared to leave their homes.”

But communities found new ways to support each other.

Daniel Henry is an HEU member from Terrace, who works part-time as a casual health care worker and full-time as a teacher. His school had to cancel its annual “Soup Feast” gathering that provides food to families in need, while sharing cultural knowledge about the ingredients.

Instead of a communal event, the school delivered soup packages to families’ doors. “This provided families a great opportunity to prepare and share a meal together at home,” says Henry.

For some members at First Nations health centres, the pandemic response also highlights disparities between them and other health care workers. While pandemic pay has been announced for most health care workers in the province, it remains unclear whether or not this premium also applies to many health care workers working at First Nations health centres.

“We put ourselves in as much risk as our colleagues who work in hospitals,” says Half. “We should be benefitting from the same supports as other health care workers.”

The pandemic intensified the challenges many Indigenous Peoples were already experiencing within the health care system and their communities – and brought to light what needs to change.

Heather Mandziuk, a nursing assistant in Burnaby and co-chair of the HEU Indigenous Peoples Standing Committee, hopes that with better understanding of Indigenous history and culture, particularly the intergenerational impacts of trauma, the system can deliver health care in a more compassionate, caring and equitable way through this crisis and beyond.

Originally published in the Summer 2020 issue of the Guardian